Possibly, in 2050 the word wastecan be removed from our dictionaries. At that time, the Dutch economy will be circular according to the government. Meaning in essence, that all raw materials are reused infinitely. In order to reach this goal, an agreement with respect to the use of raw materials has been concluded between 325 parties. Its first milestone is halving the use of primary raw materials before 2030[1].

Many are skeptical of the outcomes of this agreements. Admittedly, 38.7% of the Dutch population feels that we are on the right track, although progress is slow. Jan Jonker[2], professor of business administration at Radboud University, is more pessimistic: We do not think circular yet. Institutions, from legal to fiscal, are fully geared to the linear economy.

Amsterdam is making progress. In 2015, the municipality explored opportunities for a circular economy, which have been published in Amsterdam Circular: Vision and roadmap for city and region[3]. Dozens of projects have been started, albeit mostly on a small scale and starting from a learning-by-doing perspective.

The report Amsterdam circular; evaluation and action perspectives[4](2017) is an account of the evaluation of these projects. It concludes that a circular economy is realistic. The city has also won the World Smart City Award for Circular Economy for its approach – facilitating small-scaled initiatives directed at metropolitan goals. Nevertheless, a substantial upscaling must take place in the shortest possible time.

Below, I focus on the construction sector, which includes all activities related to demolition, renovation, transformation and building. Its impact is large; buildings account for more than 50% of the total use of materials on earth, including valuable ones such as steel, copper, aluminum and zinc. In the Netherlands, 25% of CO2 emissions and 40% of the energy use comes from the built environment.

By circular construction we mean design, construction, and demolition of houses and buildings focused on high-quality use and reuse of materials and sustainability ambitions in the field of energy, water, biodiversity, and ecosystems as well. For example, the Bullitt Centerin Seattle, sometimes called the greenest commercial building in the world, is fully circular[5]

The construction sector is not a forerunner in innovation, but of great importance with respect to circularity goals. The Amsterdam metropolitan region is planning to build 250,000 new homes deploying circular principles before 2050.

The evaluation of the projects that have been set up in response to the Amsterdam Circular Planhas yielded a number of insights that are important for upscaling: The most important is making circularity one of the key criteria in granting building permits. The others are the role of urban planning and the contribution of urban mining, which will be dealt with first.

The role of urban planning

Urban planning plays a crucial role in the promotion of circularity. It is mandatory that all new plans depart from circular construction; only then a 100% reuse of components after 2050 is possible. The renovation of existing houses and buildings is even more challenging than the construction of new ones. Therefore, circular targets must also apply here. Dialogue with the residents, and securing their long-term perspective is essential. The transformation of the office of Alliander in Duiven into an energy neutral and circular building is exemplary (photo below).

The contribution of urban mining

Existing buildings include countless valuable materials. The non-circular way of building in the past impedes securing these materials in a useful form during the demolition process. Deploying dedicated procedures enables the salvation of a large percentage of expensive materials. In this case we speak of urban mining. Unfortunately, at this time re-used materials are often more expensive than new ones. Therefore, a circular economy will benefit with a shift from taxes on labor to taxes on raw materials.

Issuing building permits

The municipality of Amsterdam made a leap forwards with respect to issuing building permits to enable circularity[6]. Based on the above-mentioned definition of circular building, five themes are addressed in the assessment of new building projects: Use of materials, water, energy, ecosystems as well as resilience and adaptivity. Each of these themes can scrutinized from four angles:

- The reduction of the use of materials, water and energy

- The degree of reuse and the way in which reuse is guaranteed.

- The sustainable production and purchase of all necessary materials.

- Sensible management, for example a full registration of all components used.

Application of these angles to the five themes yields 32 criteria. A selection of these criteria is made in each project, depending from whether the issuing of building permits or renovation is concerned, and also from where the building takes place. For instance, a greenfield site versus a central location in a monumental environment.

One of the projects

In recent years, the municipality of Amsterdam has included circular criteria in four tenders: Buiksloterham, Centrumeiland, the Zuidas (all residential buildings) and Sloterdijk (retail and trade). On the Zuidas, the first circular building permit was granted in December 2017. 30% of the final judgment were based on circularity criteria.

The winner is AM, in collaboration with Team V Architects. In their project Cross over, they combined more than 250 homes with offices, work space for small businesses and a place for creative start-ups. The project doesn’t have a fixed division between homes and offices. Reuse in future demolition is facilitated by a materials passport and by building with dry connections, enabling easy dismantling.

Need to organize learning

The detailed elaboration of the 32 criteria for circularity to be applied in tenders, covers more than 40 densely printed pages. One cannot expect from potential candidates to meet the requirements routinely. It would therefore be welcomed if the municipality of Amsterdam shared its knowledge with applicants collectively during the submission process.

I also would welcome ‘pre-competitive’ cooperation by communities with manufacturers, knowledge institutions, clients and construction partners with the aim to develop circular building. This involves for instance standardization of the dimensioning of components (windows, frames, floorboards) and the ‘rehabilitation’ of ‘demolished’ components while maintaining the highest possible value. This might be combined with a database in which developers can search for available components.

In Zwolle, another strategy is followed: the municipality, housing corporations and construction companies have formed a Concilium[7], which aims to significantly expand the already planned construction of houses, using circular principles.

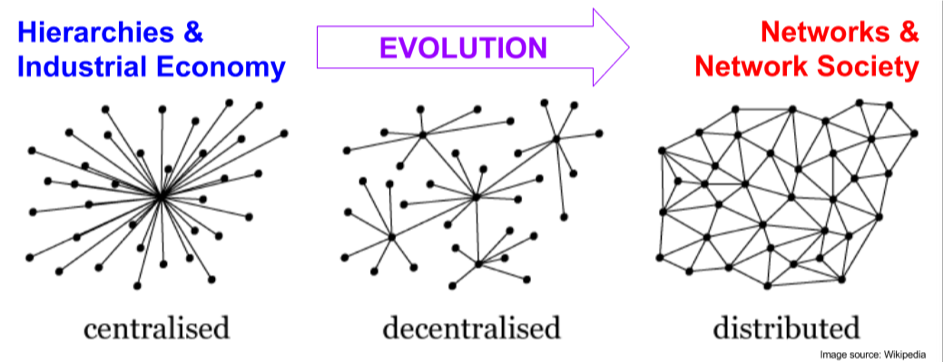

Circularity requires closing circles. Collaboration within the supply-chain is one of these.

[1]https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2016/09/14/bijlage-1-nederland-circulair-in-20

[2]https://www.duurzaambedrijfsleven.nl/circulaire-economie/27945/de-stand-in-het-land-zijn-we-al-een-beetje-circulair

[3]https://www.amsterdam.nl/wonen-leefomgeving/duurzaam-amsterdam/publicaties-duurzaam/amsterdam-circulair-0/

[4]https://www.amsterdam.nl/wonen-leefomgeving/duurzaam-amsterdam/publicaties-duurzaam/amsterdam-circulair-1/

[5]http://www.bullittcenter.org

[6]https://www.amsterdam.nl/wonen-leefomgeving/duurzaam-amsterdam/publicaties-duurzaam/amsterdam-circulair-1/

[7]https://www.weblogzwolle.nl/nieuws/61325/ambitieus-plan-voor-zwolse-woningmarkt.html

San Francisco brand of ‘sharing’ is commercial in the first place and has beside winners also many losers, for instance the drivers of companies like Uber and Lyft and those in other taxi-companies. The unprecedented influx of tourists in cities like Amsterdam and Barcelona due to the succes of one of the sharing economy icons, Airbnb, also will not contribute to its popularity.

San Francisco brand of ‘sharing’ is commercial in the first place and has beside winners also many losers, for instance the drivers of companies like Uber and Lyft and those in other taxi-companies. The unprecedented influx of tourists in cities like Amsterdam and Barcelona due to the succes of one of the sharing economy icons, Airbnb, also will not contribute to its popularity.

Other cities offer additional insight in the intermediate role of city government to enhance the ‘sharing potential’ of their towns. An striking example is Medellin, the second town in Colombia and the former center of drug trafficking, also known as ‘murder capita’ of the world. After that military shot the infamous gangleader Pablo Escobar, the city government started to repair the ruined social fabric of the town. It invested large sums in education and communal facilities, often in iconic buildings like the Biblioteca de Espagna in the middle of poor areas, to enable their inhabitants regaining some feeling of proudness.

Other cities offer additional insight in the intermediate role of city government to enhance the ‘sharing potential’ of their towns. An striking example is Medellin, the second town in Colombia and the former center of drug trafficking, also known as ‘murder capita’ of the world. After that military shot the infamous gangleader Pablo Escobar, the city government started to repair the ruined social fabric of the town. It invested large sums in education and communal facilities, often in iconic buildings like the Biblioteca de Espagna in the middle of poor areas, to enable their inhabitants regaining some feeling of proudness.

These words are from

These words are from  Technologists and urbanists

Technologists and urbanists The implementation of solutions

The implementation of solutions

I assume that the focus on technological solutions in inherent in Sidewalks Lab’s connection with Alphabet. The ultimate ambition of Sidewalks Labs is to reimagine cities from the Internet up. That is why Alphabet has created the company. In the end, Sidewalks Labs’ mission is paving the way for new services to develop or to deliver by Google.

I assume that the focus on technological solutions in inherent in Sidewalks Lab’s connection with Alphabet. The ultimate ambition of Sidewalks Labs is to reimagine cities from the Internet up. That is why Alphabet has created the company. In the end, Sidewalks Labs’ mission is paving the way for new services to develop or to deliver by Google.