Since the 1950s, there are musicians, who want to enrich country & western music by building bridges to other types of music (‘so-called crossovers’), such as European pop, rhythm & blue sand rock. From the late 20ste century, the popularity of crossovers seems to have surpassed that of traditional country & western. A person that has contributed to this is Shania Twain who thus paved the way for Taylor Swift among others. To get acquainted with Shania , listen to her rendition of ‘Man, I feel like a woman’, a song from her third album.

Back to the beginning. Eilleen Regina Edwards was born on 28 August 1965 near Ontario. She never knew her father. She was raised by mother and her stepfather, whose name she also took. He was an Oibwa, a Canadian First Nation and from his language would also come the name Shania, which she started using as a stage name around the age of 20. From the age of eight, she worked alongside her school to help earn a living for the family. She cleaned in pubs and worked with her father in forestry. Later, she became a singer in several bands with which she gained much appreciation.

Here is a clip from that time of otherwise poor quality on which she sings the song ‘What Made You Say That’, a song she did not write herself.

The lyrics of this song are here

Her Cinderella days were yet to come to an end. At her 22the, she took up caring for her younger brother and sister when her parents were killed in a car accident.

She managed to get the attention of a record company, Nashville-based Mercury, and on her 28the , she released her first album: ‘Shania Twain’. It also contained the song ‘What Made You Say That’. The record company produced a rather explicit music video with it for the time, which you can hear here.

The album was not a commercial success, but it did attract the attention of producer Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange, whom she married soon after and who was a key support on the three albums she released between 1995 and 2002.

The woman in me

The first of these (her second album) ‘The woman in me’ (1995) sold 20 million copies. Her husband had an unerring sense of marketing and replaced the country ‘flavor’ in this album for sales outside the US with ‘pop’ elements, for instance swapping violins for synthesisers. Market segmentation would continue in subsequent albums.

The two most successful songs were ‘(If you are not in for love) I ‘am outta here’ and ‘Any man of mine’, a clear example of a ‘crossover’. One of the rare pure country & western songs is ‘Whose bed have your boots been under?’, which is accompanied by a funny music video. You can listen and watch it here.

‘I’m outta here’ is the first of the two recordings from this album. This song also has a humorous video, that also has several versions. You can watch the somewhat absurdist ‘Mutt Lange pop remix’ here. In this video, drums play an important role. This was also the case in her concert tour. This song was usually closing number (before encores) and she was always accompanied on stage by a local drum band in the process. Watch and listen here:

The lyrics of this song are here

The second song from ‘The woman in me”, that you can listen to and watch here is ‘Any man of mine’

Read the lyrics here

With this song, Twain reached No 1 on the country charts in the US for the first time. You can watch a live performance filmed in Dallas. The widely viewed music video (watch here) undoubtedly boosted Shania’s acceptance as a country singer.

From the songs in this album, I picked a couple of good recordings: Come Over Here, Don’t Be Stupid (You Know I Love) and From This Moment On.

Critics were generally positive, praising the way Shania adapted country & western music to the inevitable influence of rock and pop. Others felt that the album had nothing or little to do with country & western anymore. Still others felt that Twain did not need her superficial flirtation with country & western at all to excel as a singer. Critics looking back on this album a decade later believe that she has definitively put ‘country pop’ on the map as its own genre. Taylor Weatherby of Billboard speaks of a ‘brilliant fusion of country, pop and rock’.

Up

Shania’s fourth album ‘Up’ (2002), which sold 20 million copies, plays even further into the differences between outlets. Here is the title track ‘Up’, live in Chicago.

Three different CDs were released, a green CD that has a predominantly country & western character and also contains some acoustic songs, a red CD, on which pop and rock dominate and a blue CD with a dance and South American character. Using the links above, you can compare the three genres using the three official music videos of the title track ‘Up’. I think the differences are very small.

Again, comments were mostly positive. Something for all tastes, surely seems to be increasingly becoming Twain’s (or Lange’s) trademark, but it was also noted that ‘Up’ is “too generic and emotionless for that level of diversity”.

You can now watch two other songs. The first is “Thank You Baby (For Makin’ Someday Come So Soon)”. The music video was shot at a gallery in Vancouver and released only in Europe.

You can watch and listen to this video here.

Read the lyrics here

Next, watch and listen to ‘She’s Not Just a Pretty Face’, live from Chicago. Billboard’s comments did not lie: The song is an “ultra-lightweight country-girl power anthem” but also “exquisite country pop”.

The lyrics are here

Her next new studio album came just 15 years after “Up”. Lyme disease significantly weakened her voice and she endured open throat surgery to strengthen her vocal cords. Moreover, she divorced in 2008, after Lange got into a relationship with her best friend. She remarried in 2011 with Frédéric Thiébaud, ceo of the Neslé group[1]. She did not perform again for the first time until 2012.

Now

For this album ‘Now (2017) and for the subsequent ‘Queen of me’ (2023), Shania Twain not only wrote all the songs, but she also took responsibility over the production, something her former husband did for the previous albums. Listen to from ‘Now’: ‘Life’s About to Get Good’.

You will find lyrics here

The song, which is about coming out on top after a difficult time, was well received. Billboard’s Andrew Unterberger called it ‘Come on over’-worthy (her third and best-reviewed album, 20 years earlier)

Queen of me

Netflix made a documentary of Shania Twain’s life in 2022. It was called ‘Not just a girl’, after a 2022 song that is also on ‘Queen of me’. I am showing the ‘unofficial’ music video of this song, which consists of a collage of photos and videos covering her entire life as a singer. Those who want to hear ‘Not just a girl ‘live’ listen to the (mediocre) recording in Las Vegas here.

Lastly, listen to a song from ‘Forever and for Always’ (album ‘Up’), recorded during the ‘Queen of me’ tour in September 2023. The song is about friendships that last a lifetime. I noticed for the first time that her voice was lower than before. You (finally) start to see the age (58!).

read the lyrics here

Music critics generally hold her songs, her vocal performances and her stage performances in high regard. That appreciation applies to a slightly lesser extent to her two latest albums. ‘Queen of me’ contains mostly unadulterated electro-pop. One critic notes that Twain “tries so hard to capture current trends that it already sounds behind the times”.

My next post is about one of the singers for whom Shania paved the way, Taylor Swift, whose artistry will be explored in the next two post.

[1] His name came up in another blog post of mine ear a few years members after this company was accredited as a ‘benefit corporation’, expressing that social considerations, consumer interests and nature carry equal weight with shareholder value.

These words are from

These words are from  Technologists and urbanists

Technologists and urbanists The implementation of solutions

The implementation of solutions

I assume that the focus on technological solutions in inherent in Sidewalks Lab’s connection with Alphabet. The ultimate ambition of Sidewalks Labs is to reimagine cities from the Internet up. That is why Alphabet has created the company. In the end, Sidewalks Labs’ mission is paving the way for new services to develop or to deliver by Google.

I assume that the focus on technological solutions in inherent in Sidewalks Lab’s connection with Alphabet. The ultimate ambition of Sidewalks Labs is to reimagine cities from the Internet up. That is why Alphabet has created the company. In the end, Sidewalks Labs’ mission is paving the way for new services to develop or to deliver by Google.  At first sight, students’ and employers’ interests are opposed. The recent Reimagining Education Conference at Wharton University revealed quite a different perspective

At first sight, students’ and employers’ interests are opposed. The recent Reimagining Education Conference at Wharton University revealed quite a different perspective

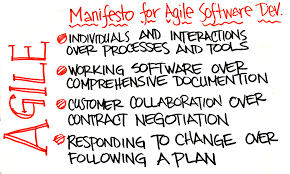

Luckmann and Prange compare the current approach to learning in universities with the development of enterprise software. The implementation of massive all-embracing software in companies seldom results in satisfying solutions. The same applies to a curriculum that has to serve hundreds of students at once. In software development the agile approach is gaining ground, which in essence is based on interaction between developers and customers, taking customers’ needs and wants as starting point.

Luckmann and Prange compare the current approach to learning in universities with the development of enterprise software. The implementation of massive all-embracing software in companies seldom results in satisfying solutions. The same applies to a curriculum that has to serve hundreds of students at once. In software development the agile approach is gaining ground, which in essence is based on interaction between developers and customers, taking customers’ needs and wants as starting point. In the same way, agile universities will put the interaction between students and teachers in the centre. Therefor they rely in a large degree on self-organization. A rich variety of teaching-learning interactions appear, mostly based on co-design. Students are getting acquainted with a broad range of disciplines and learn to search, apply and deepen relevant knowledge in projects, favourably in collaboration with parties outside the university.

In the same way, agile universities will put the interaction between students and teachers in the centre. Therefor they rely in a large degree on self-organization. A rich variety of teaching-learning interactions appear, mostly based on co-design. Students are getting acquainted with a broad range of disciplines and learn to search, apply and deepen relevant knowledge in projects, favourably in collaboration with parties outside the university.